I’ve launched upon another book design project, typesetting the letters sent home to Virginia from mid-1950 to the end of January 1951 by an Army nurse who served in a mobile hospital unit (and not just any such unit: see below). The letters themselves probably will only amount to about thirty-five pages, but between the maps, photographs, front matter, timelines and commentary I propose to add, the thing will likely bulk up up to twice that.

The nurse in question, Captain C.H. Wilson, was the maternal aunt of my best friend at Flatline, Comatose, Torpor & Drowse—he died, suddenly and far too young, years before that outfit’s fateful disfigurement and rebirth as BDS—and I have undertaken the book on behalf of my friend’s daughter, who was seven or eight when I first visited the family and who—fuck me!—will turn fifty this spring. I’ve just sent her my first draft (considerably toned down in points of snarkasm) of the proposed introduction:

Though obviously on a far smaller scale than WW II, Korea did not stint on atrocities, mainly fratricidal, although MacArthur’s people kept their hand in with the occasional civilian massacre.

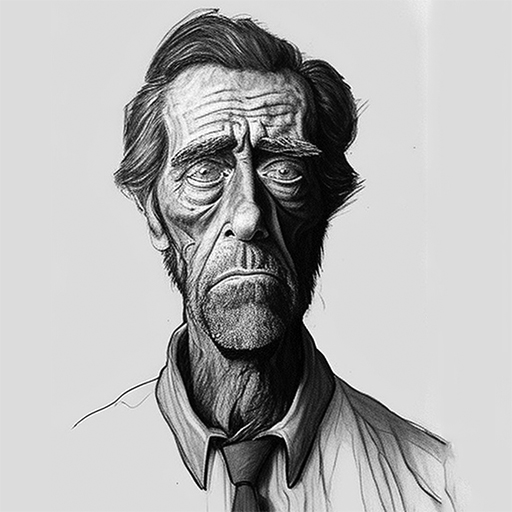

For the cover treatment I think I’ll be going with something close to this.

cordially,

The nurse in question, Captain C.H. Wilson, was the maternal aunt of my best friend at Flatline, Comatose, Torpor & Drowse—he died, suddenly and far too young, years before that outfit’s fateful disfigurement and rebirth as BDS—and I have undertaken the book on behalf of my friend’s daughter, who was seven or eight when I first visited the family and who—fuck me!—will turn fifty this spring. I’ve just sent her my first draft (considerably toned down in points of snarkasm) of the proposed introduction:

“Get up Kitty, this is war and you are in it!” On 25 June 1950 the Republic of Korea, the southern half of that partitioned peninsula, was invaded by the armed forces of its northern counterpart. In Tokyo a week later, nurse anesthetist Lieutenant Catharine “Kitty” Wilson, an eight-year Army veteran of wartime actions in North Africa, Italy and the D-Day landings, was dispatched to Korea at her insistence. These initial orders were briefly countermanded, to her indignation: “I joined the Army Nurse Corps so that I could take care of soldiers, and if I am to spend my duty hours giving anesthetics to women and children at a time like this, I might as well come home and live in comfort,” she wrote to her family from a placid berth in Occupied Japan. Three weeks later, after tugging on some strings and, presumably, having lodged an appeal to higher authority (“That gentleman thinks I’m all right because I am a Virginian”), Lt. Wilson was en route to the maelstrom.I have high hopes for the production, and it’s been interesting acquainting myself with the Korean War. Honestly, when I was a nipper in the fifties, the culture was saturated with World War II—it was our Iliad—but no one talked about Korea, even though it’s likely that there were some vets of that dustup among the fathers of my playmates. I was admittedly a somewhat incurious child, but I think Vietnam may have begun to heat up before, in my early/mid-teens I realized that Something Had Gone Down on the mainland times past. As I put it in a discarded draft of the introduction, the “police action” was “overshadowed fore and aft by the titanic global struggle that preceded it and the prolonged, demoralizing and ultimately unsuccessful campaigns by four consecutive US administrations to thwart the reunification of Vietnam.”

In the aftermath of the Second World War, having made meals of the Third Reich and the Empire of Japan, American policymakers and public alike were initially disposed to regard the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea as little more than an after-dinner mint. Within days of the invasion, the United States engineered a UN Security Council resolution authorizing international assistance, including armed force, to repel the aggression, and President Truman dispatched military assets to the scene. By month’s end, the first Air Force bombs were falling on North Korea.

The “Korean People’s Army,” or KPA, well-armed and well-trained, made short work of the South Korean troops, capturing Seoul three days into the war (the South Korean capital was to change hands four times before the eventual armistice). More alarmingly, in the first US engagement with the enemy at the Battle of Osan on 5 July, an American task force, outnumbered and under-equipped, was mauled by North Korean armored and infantry divisions. For the rest of the summer the KPA pressed relentlessly forward, to the shock of American commanders in the field and the bewilderment of the public on the home front. By September the multinational force—principally American, of course, but throughout the conflict the imprimatur of the United Nations was emphasized—found itself pinned pinned to the country’s southeast corner, the “Pusan Perimeter,” amounting to barely an eighth of the country’s area, with the increasingly confident foe battering that salient.

In mid-September, the tide of battle turned. General MacArthur’s staff engineered the amphibious landings at Inchon on the Korean west coast near Seoul, weakly defended well behind KPA lines, cutting off the foe’s forces in the south from resupply. Thereafter the fortunes of war were to seesaw wildly over the next several months. The besieged UN armies, now reinforced and resupplied, broke out of the Pusan Perimeter, the North Korean armies retreated in disarray, and MacArthur’s troops raced over the prewar partition. By October American-led forces had reached and occupied Pyongyang, the North Korean capital, and total victory, the unification of the Korean Peninsula under Western suzerainty, appeared to be within sight. Visions of ticker-tape parades must have danced in MacArthur’s head. The People’s Republic of China, of course, had other ideas.

These tumultuous months, from July 1950 to February 1951, made up Kitty Wilson’s war.

Lieutenant Wilson served as a nurse anesthetist in a “Mobile Army Surgical Hospital,” one of seven deployed during the war. As it happened, she was assigned to the unit designated “8055th,” of particular note because one of the surgeons who served with the 8055th MASH was Dr. H.R. Hornberger Jr., who, under the nom de plume Richard Hooker, published a fictional account of his experiences there as MASH: A Novel About Three Army Doctors. Two years later his novel was adapted for the screen and subsequently into a long-running television series, probably the principal reason that Korea is no longer referred to as “the forgotten war.”

Did Dr. “Hooker” and Nurse Wilson ever work together? It’s certainly possible: their stints in the 8055th overlapped. It strikes the editors as unlikely—anticipating the reader’s prurient curiosity—that our author served as a model for the film’s priggish Major “Hot Lips” Houlihan: Captain Wilson’s accounts of herself (“Soon I’ll be immune to everything but men!”) suggest that she wasn’t anything like so officious and straitlaced as Sally Kellerman’s character.

During the heady weeks between the Inchon landings and the Chinese intervention, as UN forces chased the KPA out of the south, romped over the 38th Parallel and closed on the border with China, the 8055th was there, and Kitty shared something of that renewed confidence that American might and the justice of its cause would shortly prevail. A few days before the 8055th reached American-held Pyongyang in October she wrote “After that city, there won’t be many others to occupy, unless we get designs on Manchuria.” In the event, even though she and her unit briefly made it close to the Yalu River, the UN forces were not destined to long remain north of the 38th Parallel. By the end of January 1951 Lieutenant—now Captain—Wilson had supped full with horrors (“The last twenty-four hours have been something that should never happen to anyone,” she wrote, anent the retreat from Pyongyang in December) and was ready to quit the theatre of battle. She’d already written home that “I shall not ask to leave Korea, but…I wouldn’t turn down an offer.”

Catharine Hanger Wilson was born on August 16, 1904, in Lyndhurst Virginia. She received her medical training at the Chesapeake and Ohio Hospital in Clifton Forge, Virginia, and at the Presbyterian School of Christian Education in Richmond, subsequently studying anesthesiology at the University of Virginia Medical School, where she became a registered nurse anesthetist.

When the United States joined the other belligerents in the Second World War, Miss Wilson enlisted in the US Army, serving variously in North Africa, in the grueling Italian campaign, and on a hospital ship supporting the landings at Normandy in 1944. With the cessation of hostilities she was assigned to hospitals and medical centers around the world, the US Army having acquired a large global footprint in the postwar period. At the time of the North Korean invasion in mid-1951, she was on the staff at Tokyo General Hospital where, as she relates in these pages, she fought to be included in the first planeload of medical personnel to be flown across the Korea Strait from Japan. Her experiences during the seven months following are vividly set forth in the pages to follow. Captain Wilson remained with the Army a full twenty years, leaving the colors in 1962 and serving for the next decade with the Department of Anesthesiology at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Maryland. She died on December 11, 1986 in Tallahassee Florida, at eighty-two.

A fortnight before her deployment to the war zone, Lieutenant Wilson wrote “Long ago I learned that there is no glamour in combat duty, but having a part in patching up our boys is the most soul-satisfying experience I have ever had. My desire to be where the need is greatest and to use myself up in an effort to meet that need is just as keen as it was eight years ago.” These letters from the front are eloquent testimony that her spell in the thick of combat provided ample opportunity to sate her soul—and to use herself up.

Though obviously on a far smaller scale than WW II, Korea did not stint on atrocities, mainly fratricidal, although MacArthur’s people kept their hand in with the occasional civilian massacre.

For the cover treatment I think I’ll be going with something close to this.

cordially,